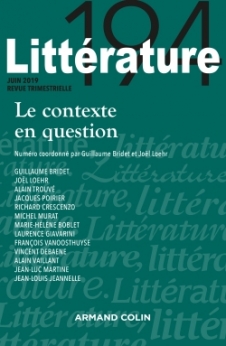

Littérature nº194 (2/2019)

Pour acheter ce numéro, contactez-nous

Recevez les numéros de l'année en cours et accédez à l'intégralité des articles en ligne.

La question « qu’est-ce qu’un contexte ? » en appelle aussitôt une autre : « qu’est-ce qu’un texte ? », qui contredit la première : si le « contexte » in-vite à une historicisation des pratiques littéraires, la notion de « texte », dans son principe même, déloge la littérature du terrain historique qui devrait être le sien. De cette contradiction, généralement inaperçue, découlent les piétinements d’une histoire littéraire qui se contenterait de se penser comme une contextualisation plus ou moins idéologique, érudite ou sociologique des textes. Pour éviter cette aporie théorique, il suffit de renoncer aux no-tions de texte et de contexte pour privilégier la notion fondamentale de communication littéraire, puis de substituer à l’histoire des contextes litté-raires une poétique historique des pratiques et des formes de l’écriture qui, sur la longue durée des sociétés humaines, doit mener à une anthropologie historique de la littérature.

The question : “what is a context ?” immediately calls for another one : “what is a text ?” in contradiction with the former : if the “context” invites to historicize literary practices, the notion of “text”, in its very principle, dislodges literature from the historical ground which should be its own. From this contradiction, generally unperceived, follows the standing about of a literary history which would content itself with thinking out itself as a contextualization of texts more or less ideological, sociological or erudite. To avoid this theoretical aporia, giving up the notions of text and context suffices to privilege the fundamental notion of literary communication, then to substitute for the history of literary contexts a historic poetics of practices and forms of writing which, in the long run of human societies, should lead to a historic anthropology of literature.