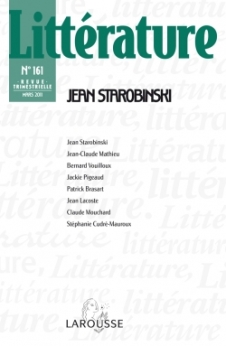

Littérature n° 161 (1/2011)

Pour acheter ce numéro, contactez-nous

Recevez les numéros de l'année en cours et accédez à l'intégralité des articles en ligne.

Après avoir esquissé une vue d’ensemble des deux grands ouvrages que Jean Starobinski a consacrés aux transformations de l’art et de la culture en Europe avant et pendant la Révolution française, il s’agit d’interroger ce qu’il nous apprend du statut de la poésie en Révolution, à travers son approche de l’oeuvre d’André Chénier. Mais la poésie s’efface alors devant l’importance de l’éloquence, dont les liaisons avec la liberté ont constitué un des axes de recherche permanents du critique de Genève ; ce qui conduit enfin à une mise au point sur la nature des rapports que Starobinski établit entre son auteur d’élection, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, et le problème du gouvernement révolutionnaire sous la Terreur.

After sketching out an overall perspective on the two main books that Starobinski has devoted to the transformations in art and culture in Europe before and after the French revolution, this study concentrates on what he has to tell us about poetry’s status in the Revolution through his work on André Chenier. But poetry then withdrew in the face of eloquence’s growing importance, a phenomenon whose links to liberty have constituted one of the Geneva critic’s major and long-standing research interests; this leads finally to an analysis of the nature of the relationship Starobinski establishes between his emblematic author, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, and the problem of the revolutionary government during the Terror.